The Next Step

BY STARR JAMISON, WITH INTERVIEWS WITH LAURA MCGLADREY AND DREW HARDESTY

In the last few years, momentum has exponentially grown to promote conversations about mental health, stress injuries, grief, and trauma in the outdoor industry. Many avalanche professionals have stepped forward to share their stories, which helps create and maintain healthy communities, with the byproduct of longevity in our careers.

Without a doubt, 2013 was my breaking point. I had been experiencing years of difficult professional and personal life traumatic events and thought I had worked through my grief and PTSD, but started having nightmares, was anxious and detached from relationships. It started with fear in my job; anticipating catastrophic events, watching over my shoulder for anti-government folks, witnessing death and disaster in the place where I once searched for solitude. My escape, pleasure and paradise of backcountry skiing also brought pain and PTSD. I lost two friends within two months in avalanches. I didn’t stop running from my fear and pain. Six months later I was on a bike tour and became a victim of a hit and run.Almost losing my arm, it was severely broken and permanent nerve damage left me unable to open my hand for over a year. Each recovery process was interrupted by the next and I couldn’t catch up until the physical trauma took me down and left me to face it all.

I had time to think about how all of these events had stacked up. As a park ranger, silence was prevalent; no one wanted to talk about traumatic events. I was told that, in the unfortunate case I needed to talk to someone, there was a chaplain, who sounded like someone distant, foreign, and disconnected from my community.We trained six months before we could travel on our own as rangers, but had no medical or pre-stress management training to manage events we may see out there. For my personal traumatic events, which were now compounding with professional trauma, I watched myself changing but didn’t understand what was happening.At the time there wasn’t a name for it and I was curious to understand more about how traumatic events affect us.

I found multipleWebsites for veterans or basic information from therapy or counseling websites.To my surprise, with much research I found no support for the outdoor industry around bereavement and backcountry accidents, no one who spoke the language of skiing or climbing. During my search for peer support, I heard stories of suicide, attempted suicide, alcoholism, divorce, and escapism. I talked through events with friends, gave them resources I had found or participated in. It was a learning process taking information from others about their events, creating our own peer support group.

This led to the creation of SOAR—Survivors of Outdoor Adventures and Recovery. In 2014 I launched the Website SOAR4life.org with the vision of offering support for accident survivors to lead healthy lives through self- care, staying connected to their communities, and continuing to adventure. This organization developed from not only my own experiences but also by compiling information and questions from other survivors and their friends and family members. SOAR embodies efficacy, connection, and hope, all of which are part of Physiological First Aid.

When I heard Laura McGladrey on the Sharp End Podcast Episode 34- Psychological First Aid, her message resonated with me. She was speaking about mental health in the outdoor industry, the topic I had been searching for. Through the Responder Alliance, Laura has become a powerful force in

pioneering stress injury training and awareness.A veteran NOLS wilderness medicine instructor, emergency department nurse practitioner, and humanitarian aid worker, McGladrey works at the University of Colorado as a nurse practitioner with fire, ems and law enforcement officers and systems who have been impacted by traumatic stress. She has piloted programs with Eldora and Monarch Ski Patrols and now works with rescue teams, ski patrols, snow scientists, guides, and national parks teams to identify and mitigate stress in- juries on teams. This year you’ll find her hard at work in Yosemite, Denali, Rocky Mountains and the Tetons.

With curiosity I dug a bit deeper into the Responder Alliance’s Website and learned that it has a mission to advance national conversation on stress injuries in rescue and outdoor culture. Laura is training Ambassadors in av- alanche, ski patrol, search and rescue, and guiding communities to recognize and talk about stress impact. I was inspired and wanted to be part of this for- ward movement, combining their mission with my experience and passion. I found myself in Leadville, Colorado, in the fall of 2019, with other guides, rangers, patrollers, firefighters, law enforcement rangers, and avalanche folks, training to become a Responder Alliance Ambassador. Laura packed two weeks of information into three days of training.The energy, ideas, and col- laboration were innovative and inspiring.

I was asked to speak about my experiences and SOAR at the 4 Corners SAW in Silverton, CO. Inspired and now an Ambassador I jumped right in, discussing trauma formation and how it plays a role in our careers. I high- lighted others who have come forward to share their stories about traumatic stress injuries, then discussed how stress injuries are formed and mitigated while also discussing the momentum of mental wellness in the avalanche/ ski patrol community. I was inundated with follow-up questions from attendees and discussions on preparedness for the inevitable in our careers. Do you continue with the old ways of “debriefing” and how do we prepare for these events that inevitably affect us?

In my presentation at 4SAW, I included excerpts from a podcast from the Utah Avalanche Center, hosted by Drew Hardesty. Drew mentions the idea of Pre-Traumatic Stress Management. He says,

“Rather than waiting for teams to be surprised by overwhelming events and scramble to find someone to ‘debrief them,’ why not start the season with a pre-traumatic stress plan and practice for it? We train for rescue, beacon searches, etc. therefore we need to be talking about stress injuries and anticipate these events.”

Pre-Traumatic Stress Management is a term that McGladrey and Hardesty often kick around. In a collaboration of thoughtfulness and years of experience, together they are determined to move this from a post to a pre movement.

Follow up emails and conversations from 4SAW and my own inquisitive- ness led me to query Laura and Drew for their insights:

SJ Pre-Traumatic Stress Management, where do we start with our teams?

LMG We’ve never seen the term stress injuries used for the avalanche community, and I don’t think we’ve named these exposure patterns for forecasters. It seems very pertinent to the conversation. We’ve identified that awareness, common language, and early recognition, as well as operational use of Psychological First Aid are the components of pre-traumatic stress management,

SJ So, what do you call it?

LMG Awareness, there’s something important about naming it. Once you can name it, you can recognize it, you can start to heal. If you can’t name it, it feels like it’s just something wrong with you. Naming the impact of the exposure and loss actually allows you to connect and make different choices. It’s unrealistic to watch people you’ve skied with, that you’re responsible for, that you’ve partnered with, injured and killed doing exactly what you love to do and not be affected by it. Gravity doesn’t work that way.

SJ Stress injuries, how do they play a role in trauma formation?

LMG This is the language that the military introduced in combat and operational stress first aid.We use it now in structural fire, law enforcement, and EMS. NOLS Wilderness Medicine, thanks to Tod Schimelphenig’s leadership, now has a section on Stress Injuries that fits squarely between head injuries and chest injuries.We saw Stress Injury introduced in Accidents in North American Mountaineer- ing this year as climbing injury type. It’s fair to call this an exposure injury, but it’s more than that. It also happens with the wear and tear of decision-making, responding and depletion. If you’re a highway forecaster in the midst of the March 2019 avalanche cycle, closing roads, responding to one avalanche after another and the whole state is looking to you, you could sustain this injury without ever seeing a traumatic event. But add that kind of depletion to a bad call, or overwhelming trauma and you have the recipe for significant injury formation.

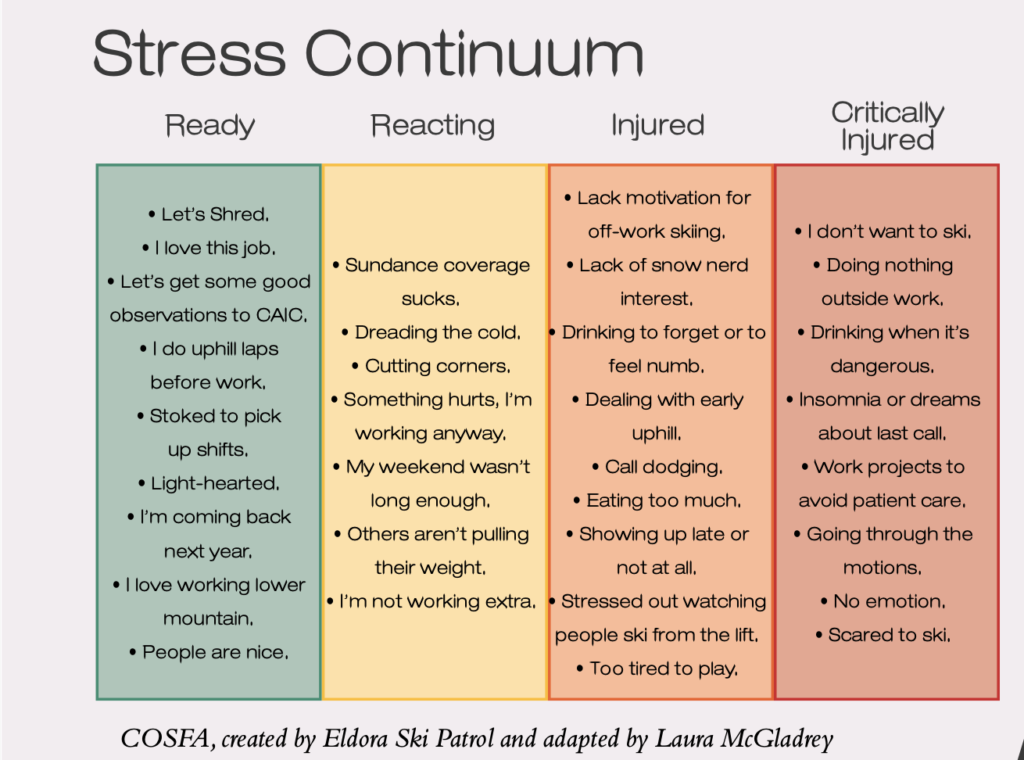

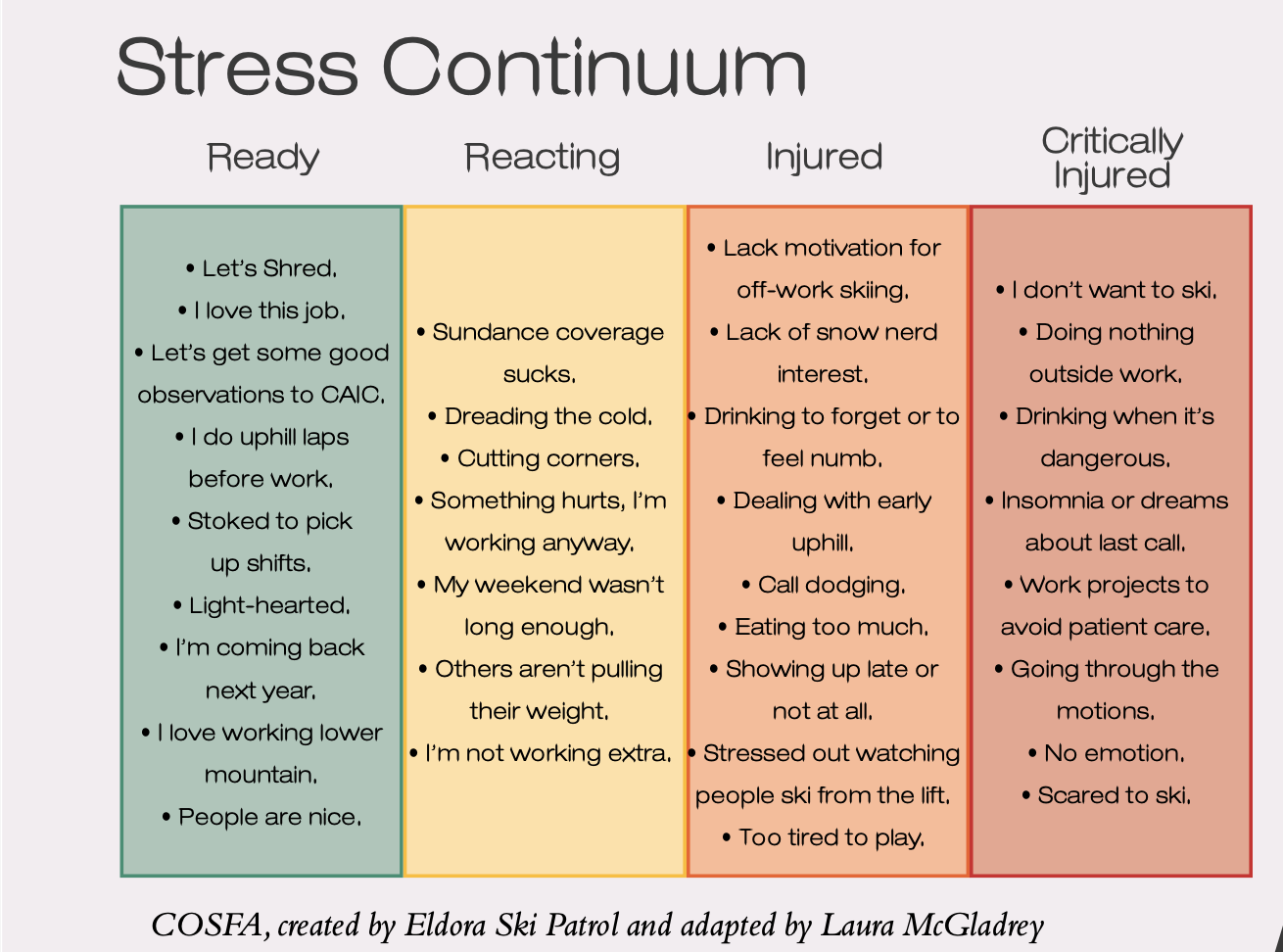

These injuries occur on a continuum.They aren’t one size fits all. One of our great challenges in supporting this injury type currently is that we only have one name for it; Post Traumatic Stress Injury or PTSD, and the reactions associated with PTSD are very real, but represent a serious injury type.We haven’t had a language to recognize and identify early changes in this injury type.The stress continuum is designed to be a common language that responders could use to first recognize stress impact before it ever becomes an injury.

Stress Continuum

Creating teams that folks want to come home to when hard things hit might be the single most important thing we can do to mitigate traumatic stress. Sometimes it’s the hardest.

SJ How do stress injuries develop?

LMG There’s a formula, actually. Folks think if you do critical incident support you have a magical ability to determine when folks will get hurt. It’s not like that. Like so many things in avalanche, it’s pattern recognition and once you start looking for it you’ll see it everywhere.

Stress injuries are formed when a stressor or series of stressors overwhelms the person experiencing its capacity to integrate it or make sense of it.This means stress injuries occur in a state of stress. That means look for the folks when something tough happens who are stressed, depleted and don’t feel like they can handle what’s in front of them.That’s whom traumatic exposure usually hurts.

The human machine is actually made to respond to stressful situations, such as one’s car sliding off the road or a taking a small ride in an avalanche, and then skiing out of it. Each time that happens we mount a physical response, overcome, then send out a chemical ‘all clear’ signal and forget all about it.

It’s not until moments when our brains register that ‘this could be really bad,’ or when we are isolated and can’t respond (think swept in the avalanche without a witness) that our brain register threat to life. At that moment, there’s a failure of the all-clear signal and we tend to mount a survival response. In those moments, even if we watch someone else caught in a slide, we will store the memory of it happening to us. At that moment, we flip a switch from living the lives we were living to survival.The brain and body’s primary goal becomes survival, which means rather than spending our lives en- joying skiing, falling in love and creating we are hyper vigilant, iso- lated, exhausted with less and less joy for the things we used to love.

SJ Why the mission to change the way we talk about traumatic stress?

LMG An adage that we work with often in my clinical work is “awareness, then choice.”

If you don’t know that your life’s on fire, you won’t do anything about it.

If you’re a patroller who has a short fuse, is feeling burned out on forecasting, dreads coming to work, but can’t do anything else and thinks it’s just how everybody feels at a certain point in their career, then you won’t try and change it. So often what we see as stress impact gets assigned to personality.We think,“that guy or gal is just toxic. Let’s get him out of here because it sucks to work with him.” We don’t say, “Man, that guy is really affected by losing half of the friends he started with, and weighed down with the responsibility of making these calls day after day. Let’s support him.”

Until we name it, we won’t recognize it and we can’t do anything about it. There’s something important about naming it. Once you can name it, you can recognize it, you can start to heal.

It’s like recognizing that chest pain,shortness of breath,and radiating pain have a name. Ah, heart attack. Right. I know what to do.

SJ We are starting to see the stress continuum in ski patrol locker rooms, Ski Patrol Magazine and at SAW events. Tell us more about the continuum and have you created one for avalanche forecasters and guides?

LMG The continuum was originally based on one used by the marines in Combat and Operational Stress First Aid.We have been calibrating it for Patrol, Rescue, and NPS climbing rangers and now avalanche. It has four stages Ready (Green), Reacting (Yellow), Injured (Orange) and Critical (Red). Eldora Ski Patrol is the first patrol I worked with who crafted this continuum for the Ski Patrol and Avalanche community. It was pretty simple. We put up four colored pages in PHQ (Patrol Headquarters) and let folks fill them out for patrol. At morning meeting, when patrollers do personal risk assessment, they take note of what color they are on the continuum. If folks are creeping up into the orange, they notice it and can take steps like taking some time off, connecting with each other or letting the patrol director know in order to take action.We also set a goal of finishing in the green as much as we can. Having a language and a goal to be healthy seems to be changing culture.

No we haven’t created a forecaster or guide- specific continuum yet, but we’re working on it. I’m hoping someone reading this thinks,“This is what I want to do,” and reaches out to do it.

SJ Drew, as a long-time forecaster can you give us an example of what stress injuries you’ve seen or experienced in your career?

DH What’s interesting is that we have different kinds of forecasters and responders and the stress injury plays out differently.

Each niche of avalanche forecasting—backcountry, highway, and ski area avalanche forecasting has its own type of stress, but they can all involve sleep deprivation, uncertainty, continuous attention to detail, perhaps even some close calls or accidents. There can be cumulative stress and a lifetime of exposure that can lead one to- ward traumatic stress without proper attention and support. Each of us assumes a great weight of responsibility to protect the public, commerce, and one another.

A good example is the recent early February storm in the Wasatch Range. Upper Little Cottonwood Canyon received nearly 7” of SWE in 50 hours with sustained strong west winds. Nearly every avalanche path ran naturally or with artillery.The backcountry forecaster issues the High to Extreme danger rating and tells people to hide under the bed.The highway forecaster gets very little sleep because the town of Alta is interlodged and the road is closed for 42 hours.The plow drivers then work to clean up the debris while underneath all of the avalanche paths that have run…but there is always some uncertainty here.

What does seem to be common for all is the weight of the decisions that forecasters of all types have to make. If you’re a backcountry forecaster and you blow a forecast, someone might get hurt or killed.The same is true on a highway if a natural avalanche knocks cars off the road. No different for the patroller who keeps terrain open resulting in an inbounds avalanche or the guide who takes folks out only to have them swept and killed. It’s weighty, and the weight accumulates.

I often joke that I get paid to pay attention but the truth of the matter is that paying attention is a lot of f—ing work. Paying attention all the time is hyper vigilance. Paying attention during continuous weather causes tremendous strain. It can wear on you. Heuristics are shortcuts that we use because we have to make decisions all the time and paying attention to everything all the time is exhausting. Some call it “lazy,” others “efficient.”These shortcuts work most of the time but that’s not good enough. Regardless, one must pay a high level of attention to the snow and the weather because avalanche conditions can turn on a dime…and because we know what’s at stake.

There is this idea of message fatigue and inadequate patience. “You and the public get tired of saying the same things over, Depth hoar, facets at bottom…blah blah blah and nothing happens.You stop paying attention or let desire cloud judgment and then you blow it.”

SJ Laura, you mention Psychological First Aid as a component of Pre-Traumatic Stress Management. What is it?

LMG Psychological First Aid is basically a toolkit for folks respond- ing to others who have been overwhelmed by what’s in front of them. They are tangible steps, stuff you might do anyway if you knew why it matters, to help folks fire off the all- clear signal we just talked about. In 2015 we formally added this injury type to our curriculum at NOLS Wilderness Medicine. We’ve been teaching folks for decades what to do to support and stabilize physical injuries. Now it’s time to have something up our sleeves for early intervention in psychological injury, like when you come on scene at an avalanche and see a partner with the thousand-mile stare.We should consider them injured too, stress injured. Dale Atkins wrote about this a few years ago in TAR 36.2, where he outlined the steps of PFA (psychological first aid). It’s really worth going back to review. I’d like to see us teaching this in avalanche education in the next few years.

SJ At the end of my 4 SAW presentation, I was asked in a panel discussion “what advice in one word would you give someone dealing with traumatic stress” and my answer was, “connection.” Can you tell us your thoughts on connection and how it is a tool for pre-traumatic stress management?

Rather than waiting for teams to be surprised by overwhelming events and scramble to find someone to ‘debrief them,’ why not start the season with a Pre-Traumatic Stress Plan and practice for it?

LMG We know that in the traumatic stress literature, the single most important factor in how injured you will be after you experience a traumatic exposure is your level of social connectedness.This means that it matters if other people know you and have a sense of how you’re doing.

One of the most impactful stories I’ve heard occurred after an inbound avalanche in Colorado where a patroller was killed. The local clinician showed up to the locker room and said,

“You’re a family and families have what it takes to get through this.This is grief and you know what to do. I’ll be back tomorrow to check on you.” It brings us back to the basics. Creating teams that folks want to come home to when hard things hit might be the single most important thing we can do to mitigate traumatic stress. Sometimes it’s the hardest.

What I candidly believe is it’s crucial to have your own peer support team, not necessarily from professionals. [We need] people to ground things with because that is our only real technology for integration of grief and trauma, the weightiness. This is our job, to do that for each other. I think that’s where we are moving in debriefing, instead of bringing people back into a hot topic that may trigger them.The old model is “we will wait till something bad happens, then come in with an eraser, and make it not bad.”

SJ How do we prepare for the worst? Tell us your ideas on pre- traumatic stress management training?

LMG This is where we need to break new trail. In all rescue teams that I work with, there is still near-universal agreement that we should only wait until after an event to support the traumatic stress, usually by an outside ‘expert’ that nobody knows. Nothing could be further from the truth.

We can plan on traumatic things happening as backcountry, patrol, and highway forecasters, even as guides.We don’t want them to happen, but it’s not possible to eliminate all risk. If we know that stress injuries occur in a place of stress, then the innovation should be to reduce stress, both occupational stress and life stress, and build capacity to respond to hard things. If you see yourself or your team getting depleted by early open or a continuous storm cycle, pay attention to the sleeplessness, the strain, the lack of connection, and the feeling of over- whelm. See what you can do about it.

We know traumatic events are going to occur on the teams and areas where we work and play. It is rare for any of the teams I work with to get through the season without at least one fatality. Rather than waiting for teams to be surprised by overwhelming events and scramble to find someone to ‘de- brief them,’ why not start the season with a Pre-Traumatic Stress Plan and practice for it?

If you could predict next week that you were going to have one of the hardest most difficult moments of your life, could you look around and know who your people are and the level and connection you have with these people? If you don’t have one or two people this makes you so vulnerable to shame, regret, moral injury.The people you come home to are the predictors of how well you integrate trauma. Not the people who come in and spend two hours in your critical incident debrief.

I think in decision-making and avalanche, the more you en- gage in those resources to get folks to a point where they feel like they have enough [resources] for the situation ahead, have something to offer, they are connected to the people and can stay present throughout the whole scene, the better the deci- sions they will make in real time.That’s actually an operational outcome. If we could pair how important these resiliency factors are to pre-resourcing we would have it.

As this movement gains traction, start by taking a look at your team and yourself and determine where you are in the continuum. Do you have appropriate tools in your box when the inevitable happens?

If you want to learn more about these tools and topics check out responderalliance.com,SOAR4life.organdamericanalpineclub. org/grieffund

(originally published by The Avalanche Review)

[…] and FamilyStrong social connections are one of the most important factors in recovering from a psychologically traumatic event. Having friends and loved ones who care about […]