How Cormac McCarthy made a deal with the Devil...and got the better end of the deal

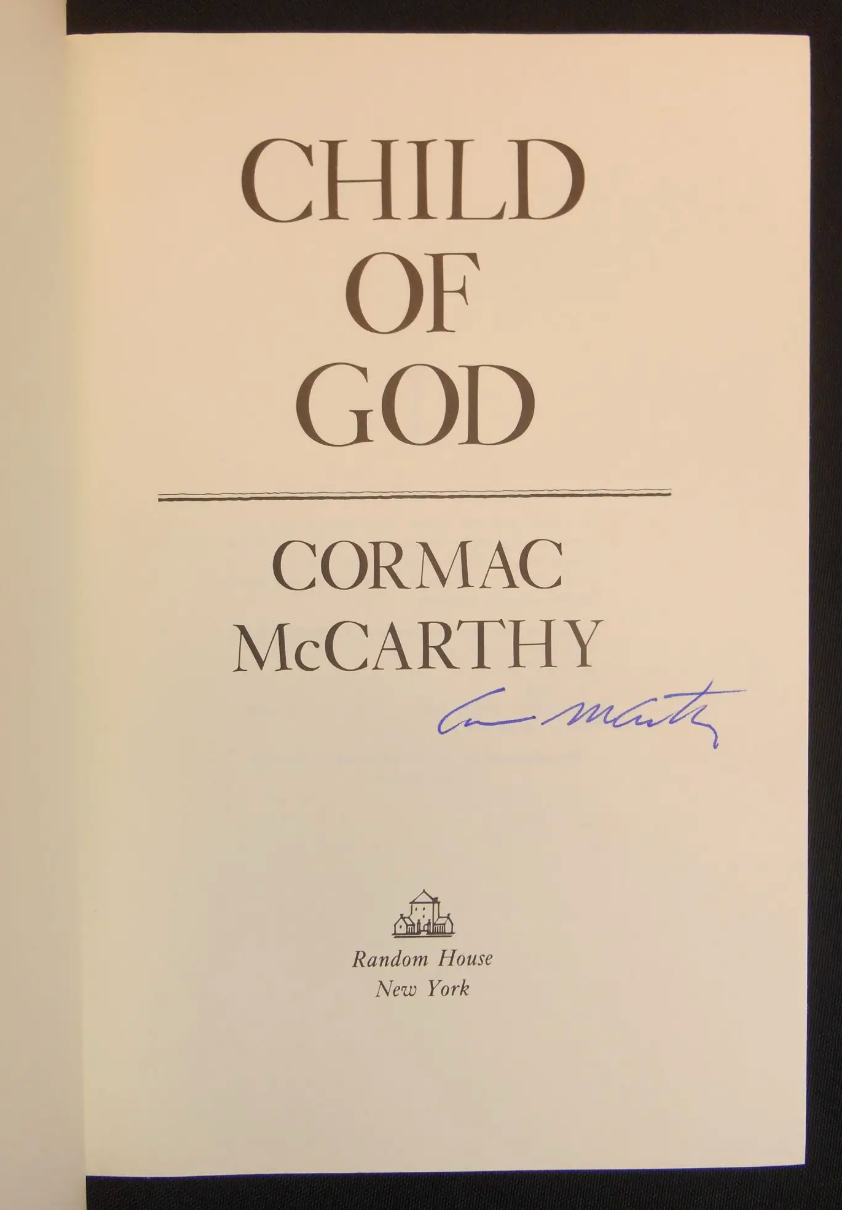

It was just before midnight, 1974, when the devil - Scratch - appeared to Charlie McCarthy. McCarthy had just written Child of God (a book on loneliness, madness, depravity and other acts unfit for this polite audience) and Scratch saw some potential. He offered McCarthy the opportunity to be the greatest novelist, no - writer - of all, should he - no - not deliver his everlasting soul - but instead make the devil a central character in all of his books. McCarthy agreed at once, and asked no questions, well aware that his soul had become vestigial at best.

The devil whispered into McCarthy's ear for The Crossing -

They were running on the plain harrying the antelope and the antelope moved like phantoms in the snow and circled and wheeled and the dry powder blew about them in the cold moonlight and their breath smoked palely in the cold as if they burned with some inner fire and the wolves twisted and turned and leapt in a silence such that they seemed of another world entire. They moved down the valley and turned and moved far out on the plain until they were the smallest of figures in that dim whiteness and then they disappeared.

Now the devil appears in many forms - senseless violence, anarchy, singular manifestations of war, unspeaking whirlwinds. As Abram became Abraham, Charlie-now-Cormac McCarthy held up his end of the bargain. You’ll recall Chigurh (below), the principled embodiment of Evil in No Country for Old Men, the world entire* in the post-apocalyptic novel The Road, and the fiddling (what else would he play?) Judge in Blood Meridian.

And yet.

McCarthy left a pinhole of light in all of the novels, with more than dramatic tension between pure evil and, simply, compassion. The young son in The Road - again and again - demonstrates compassion to others, even at his (and his father’s) great peril; the Kid in Blood Meridian demonstrates again and again clemency for the heathen and at-times (questionable) restraint with his own gang of scalphunters; even with the Judge himself; John Grady Cole’s infinite love toward the young epileptic whore Magdalena with a heart of gold in Cities of the Plain (Genesis 13). And on and on.

So what to make of this everlasting tension between evil and compassion?

See you next week -

Drew

The views and opinions expressed in this space are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any other agency, organization, employer or company.