Cormac McCarthy's Dream

This week's Meditation was originally titled The (Continued) Death of Expertise.* I continue to come across arguments and studies that diminish experience, regarding it as something of a hindrance in judgement and decision-making and that novices are equally good at choosing the "right course of action" as experts. (Do let me know if you have any thoughts on the matter; the piece is only half finished.....)

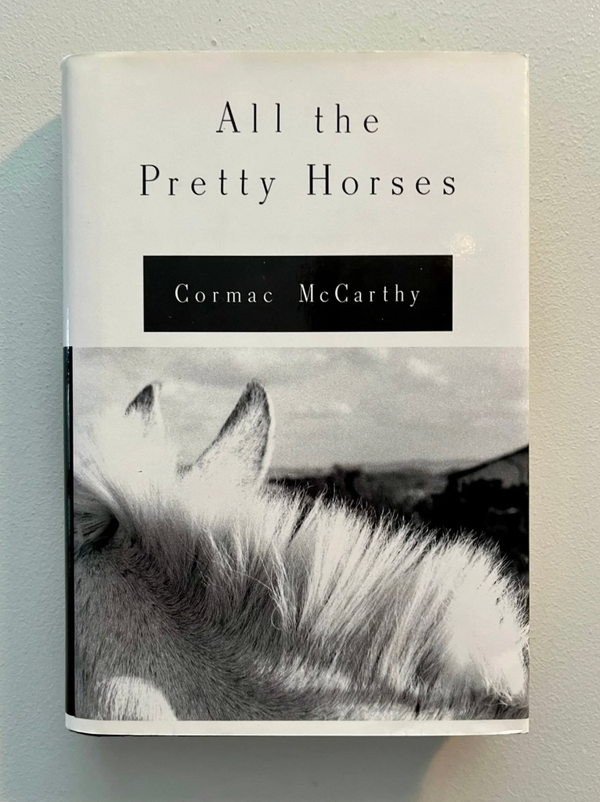

But I learned that the author Cormac McCarthy passed away at the age of 89 at his home in Santa Fe on Tuesday. My fears that he took his own life were quickly calmed and I am grateful for this. (The Sunset Limited and Stella Maris, anyone?)

And so instead I'll leave you with two thoughts on someone whose influence upon my writing and perspective on the world is, well, beyond words.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Over the years I came to believe that Cormac McCarthy made a deal with the devil. It's just that he got the better end of the deal. In return for becoming the greatest novelist in history, he agreed to make the devil one of the lead characters in his books. Consider Judge Holden, Anton Chigurh, and a post-apocalyptic Hobbesian world as clear and immutable evidence.

Thank you, Cormac. May you rest with occasional peace. You'd be bored otherwise.

Why should an avalanche forecaster care about Kekule's Dream?

McCarthy's 2017 essay The Kekule Problem is primarily concerned with the nature of consciousness; in particular, the avenues of communication, if you will, between our unconscious and our conscious selves. He writes,

I call it the Kekulé Problem because among the myriad instances of scientific problems solved in the sleep of the inquirer Kekulé’s is probably the best known. He was trying to arrive at the configuration of the benzene molecule and not making much progress when he fell asleep in front of the fire and had his famous dream of a snake coiled in a hoop with its tail in its mouth—the ouroboros of mythology—and woke exclaiming to himself: “It’s a ring. The molecule is in the form of a ring.” Well.The problem of course—not Kekulé’s but ours—is that since the unconscious understands language perfectly well or it would not understand the problem in the first place, why doesnt it simply answer Kekulé’s question with something like: “Kekulé, it’s a bloody ring.” To which our scientist might respond: “Okay. Got it. Thanks.”

Why the snake? That is, why is the unconscious so loathe to speak to us? Why the images, metaphors, pictures? Why the dreams, for that matter.

McCarthy's argument is that our unconscious selves perhaps date back to a million years whereas language is only a recent, and imperfect, construct. And I choose my words with care. He goes on to say,

Apart from its great antiquity the picture-story mode of presentation favored by the unconscious has the appeal of its simple utility. A picture can be recalled in its entirety whereas an essay cannot. The log of knowledge or information contained in the brain of the average citizen is enormous. But the form in which it resides is largely unknown. You may have read a thousand books and be able to discuss any one of them without remembering a word of the text.

Does your unconscious make better decisions than you?

It has long been my philosophy that, standing at the top of the northeast chute of Box Elder Peak in American Fork Canyon, you won't exactly remember the details and the data of the snowpack, but you will remember exactly how the avalanche forecast made you feel: imagery, metaphor, parable, emotion.

Remember this - and remember the snake coiled in a hoop with its tail in its mouth - when you read an avalanche forecast this winter.