Breaking Strength

I’ve been thinking about writing on the concept of Margins lately. Not so much to define and defend them, but to point out how expensive, cumbersome, and inefficient they can be. Tattoo’d on every technical rescue member’s arm is the Commandment “Thou Shalt Adhere to a Static System Safety Factor of 10:1” But why spend $100 when you only have to spend, say, $25?

The going philosophy in the Tetons was that if you brought the ten essentials, you would probably end up using them.

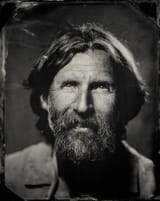

(pc: RFR)At best, margins should be directly proportional to one’s Uncertainty of the Very Bad Thing (VBT) happening. But Uncertainty of what? The probability of it happening? The timing and location of the VBT? The nature of The Very Bad Thing? One’s resilience to the VBT? And so on…Optimally (and I choose this word with care), the margin would accordion in and out depending on the dynamic, ongoing situation and accordion in and out depending on the players in the game, no?

So my plan was to reach out to a high angle rigging expert, a civil engineer, and a financial analyst. As it played out, I started and finished with Mike Gibbs, owner and lead instructor for Rigging for Rescue. I’ve known and discussed Risk with Mike for years. RFR’s mission is to offer technical ropework seminars focused on critical thinking and systems analysis to build effective rescue systems. And this - "Rigging for Rescue’s advances come not from technocratic gadgetry but by finding and reapplying knowledge that has been lost to us since the days of shipping by sail, farming by horsepower and engineering on a human scale that have passed us by. The content may seem revolutionary, but it is primarily the renewal of the knowledge that previous generations found essential for life and their livelihoods." That is worth another read. Trust me.

And then the conversation took an interesting turn.

In discussing mission profile analysis, Mike reminded me that one looks at people, equipment, and environment for failure points. (This is an oversimplification of Ishikawa’s Man (People), Machine, Material, Method, Measurement, and Mother Nature.) Even though we know that failure is in itself a complex process, we noted with wry amusement that many of us look and argue about Breaking Strength of webbing, when we should be looking at the Breaking Strength of ourselves. And I don’t mean that figuratively. DJ, one of my old colleagues at Jenny Lake, was a gifted and accomplished collegiate athlete who brought his training regimen to work. "I train to failure on my own time so I have that margin of strength for when it counts."

A few years ago, I spoke with the backcountry partner and would-be-rescuer of an avalanche victim. The victim died of asphyxiation. The partner, with surprising insight and accountability, admitted that he was just not strong enough to dig effectively into the debris pile to rescue his friend. “I was out of shape and not physically prepared for what might happen.”

I thought about this as I was dogging it uphill in the heat today.