A StormChaser's Take on Forecast Error

January 5, 2019 is a day I’ll never forget. I issued a Low avalanche danger for the Wasatch backcountry. By late afternoon, I learned that eight people had been caught and carried in shallow wind slabs. In Broads Fork of Big Cottonwood Canyon, two people were simultaneously caught. One was critically buried and suffered a temporary head injury, but ultimately rescued and evacuated from beneath the Blue Ice avalanche path by her soon-to-be fiancé. Each of these avalanches were shallow drifts of wind blown snow failing on weak faceted grains. The wind slabs were sensitive and often triggered from below. As the forecaster that early morning, I had felt that there was little snow available for transport and the pre-frontal winds weren't due to arrive until late afternoon (they arrived early). Needless to say, many people - including this forecaster - were surprised. I am thankful that there were no fatalities. This event led to a great deal of soul-searching and finally led to an essay, On the Nature of Forecasting, and Why We Get it Wrong, which naturally led to a presentation as well as a podcast An Economist, a Meteorologist, and an Avalanche Forecaster Walk into a Bar…. I’ve given the talk to professionals and the public, and to avalanche forecast teams in the US and Canada. My remark I hope to never give this talk again highlights what we know to be true: The surest way to make God laugh is to apprise her of your plans.

Not long ago, Larry Dunn (retired meteorologist-in-charge at the SLC National Weather Service and long time backcountry skier; he's in the podcast mentioned above) sent me a couple of papers by meteorologists who had looked into the challenges of forecasting. One of them had more math than I wanted, but their take-aways were eerily familiar. I wish to highlight a couple of points Charles Doswell makes in his excellent paper Weather Forecasting By Humans - Heuristics and Decision-Making. (If this is your niche, I HIGHLY recommend reading this). It was initially published on New Year’s Eve 2003, a little over a year after Ian McCammon presented his seminal paper Evidence of Heuristic Traps in Recreational Avalanche Accidents in fall of 2002. Apparently fools seldom differ (insert laugh emoji here).

So...

~~~~~~~~~

On the Role of Forecaster Bias (direct from Doswell below)

As discussed, the aim of research is to reduce the area of the ellipse (of uncertainty); that is, to increase the accuracy of the forecasting system. However, it is the role of a policy maker to determine the ratio of false negatives to false positives. That is, someone must decide what is the optimum ratio of false negatives (under-forecasting) to false positives (over forecasting).Generally in weather forecasting, false negatives are seen as a less desirable outcome than false positives (‘‘false alarms’’), because they are associated with the unfavorable notion of an unforecast weather event, perhaps with casualties as a result. False positives have their own costs that are not necessarily trivial, but generally do not usually cause casualties. This asymmetry in the perceived penalties for the two types of forecast errors means that it is common for the threshold to be pushed toward false positives .

~~~~~~~~~~

The Forecast, the Hindcast and the Nowcast

So much has been made of the challenges of forecasting that perhaps it has been easy to overlook the veiled problems with the Hindcast and the Nowcast. I’ve touched on the former in a previous essay called Hindsight 20/40. In essence, I wanted to look at how - upon looking back at an event - the investigators came away with the wrong lessons.

With the Nowcast, however, Doswell notes that we can be fooled with our analysis of the current conditions; (1) in general owing to natural uncertainty because the instruments used to obtain them are imperfect, and/or (2) that the distribution in time and space is inadequate (sampling error). With the initialized conditions (this day and age), one simply attaches a (weather) model to produce an 'outcome' .

But what if the model is right but your assessment of the initial conditions is wrong? Ever snapped a bearing on a map, followed it for hours and later realized that from the outset, you were not where you thought you were?

~~~~~~~~~~~

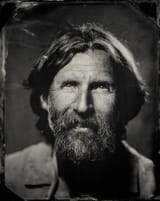

Charles "Chuck" Doswell. He may be the OG Storm/Tornado Chaser; worked for NOAA and as a professor and researcher; the list goes on and on. He was not known as a ‘company man’; rather as someone who left convention down the road. It didn’t come as a surprise that his avatar was Guy Fawkes. I reached out to him to chat forecaster error but never heard back.